|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

| Help

Solomon Islands Legislation Handbook 2005 |

SOLOMON ISLANDS GOVERNMENT

THE LEGISLATION HANDBOOK

The Legislation Handbook contains legal principles and conventions by which the Permanent Secretary must be guided. It also clarifies the procedures necessary for developing good legislation.

The Permanent Secretary is crucial to good governance and responsible for ensuring that the agenda of the Government of the day is implemented. It is also the role of the Permanent Secretary to ensure that the public servants are adhering to the laws and conventions of the Solomon Islands.

This Handbook and its companions The Cabinet Handbook, The Ministerial Handbook, The Parliamentary Handbook and The Permanent Secretary’s Handbook will be revised when necessary to reflect changing technological and other needs over time.

I ask that ministers and officials ensure adherence to the principles and procedures outlined in the Handbook. The Attorney General and his Office, and, the Secretary to Cabinet and the Cabinet Office staff are available to advise and assist.

(Hon. Sir Allan Kemakeza, MP)

Prime Minister

Table of Contents

FOREWARD

1. WHAT IS LEGISLATION?

2. PRIMARY LEGISLATION

Initial Cabinet Approval

Responsible Officer or Instructor

The need for Consultation

Preparing the Bill

Submitting instructions to the Legislative Drafter

Importance of Clarity

Explanatory Memorandum

Regulatory Impact Assessment

Presentation to Cabinet

3. FROM APPROVAL OF THE BILL BY CABINET UNTIL IT HAS BEEN PASSED BY PARLIAMENT

Procedure through the House

The First Reading

The Second Reading

The Third Reading

4. SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION

How Subsidiary Legislation is made?

Laying before Parliament

1.1 It is the Permanent Secretaries who are responsible for ensuring that that the legislation under which they are operating is current and effective. As a result, it is these officers that must provide guidance to their ministers on a programme of proactive regulatory and legislative reform.

1.2 It is also the role of the Permanent Secretaries to implement the agenda of the government of the day including any new primary or subsidiary legislation. It is therefore very important that all senior government officials understand the nature of legislation and the manner in which it is formed.

1.3 The term “legislation” is a collective term for ‘laws’ and includes both “primary” and “subsidiary” legislation.

1.4 Primary legislation is law which is voted upon and passed by a body with legislative authority. In the Solomon Islands, the National Parliament has been given legislative powers under the Constitution. Provincial Assemblies have also been given legislative powers as a result of the Provincial Government Act 1997[1].1.5 Before a law has been passed by Parliament it is called a ‘Bill’. After it has been passed and received the assent of the Governor General it is known as an ‘Act’.

1.6 Subsidiary legislation is law made under powers contained in primary legislation. Often powers are delegated to a Minister or another body by Parliament to make by-laws, regulations, rules, orders, declarations or other instrument. These have the force of law and are known as subsidiary legislation. An example of primary legislation is the Public Service Act, which was passed in 1988 and under it are various pieces of subsidiary legislation such as the Public Service (Overseas Service) Rules and The Public Service (Compulsory Examination) Rules.

2.1 The preparation of legislation involves three main stages:

· The process up to obtaining the approval of the Cabinet for the introduction of a bill in Parliament.

· The steps from approval of the Bill by Cabinet to it being passed by Parliament.

· Final steps to make the Act operative.

2.2 The path leading up to obtaining the approval of the Cabinet for the introduction of a bill into Parliament also involves a series of steps which are outlined in detail in the Cabinet Handbook. The first step is the identification of a need for legislation. This need may result from:

· the development, or change, of policy on certain issues

· a need to comply with international undertakings and obligations

· a need to update existing legislation in line with new ideas and technologies

· a need to close a loophole or to improve procedures;

2.3 Whilst the need for new or amending legislation may be identified by Government Ministers, the Cabinet, officers within Departments or persons or organisations outside of government, proposals can only come to Cabinet through the responsible minister.

2.4 The passage of the development of legislation is time-consuming and difficult. It is therefore important that the proposer has given proper consideration to the purpose and ends that need to be achieved, and whether they could be better, or more adequately, attained by subsidiary legislation or purely administrative means. Legislation should not be proposed simply to give a matter “visibility”. The limited drafting resources of the Legislative Drafter within the Office of the Attorney General and the time available for government business in Parliament must be used for proposals that cannot proceed without legislation. The Attorney General’s Office is able to advise on the need for legislation in order to implement a proposal.

Initial Cabinet Approval

2.5 Where there is a proposal to legislate on a subject that would represent the breaking of new ground, new policy or a change to existing policy, the member of the Cabinet responsible for the subject should put a brief memorandum before the Cabinet setting out the main points on which legislation is proposed and seeking approval for a Bill to be drafted. Reference should be made to the Cabinet Handbook.

2.6 Minor amendments or simple pieces of legislation may however be prepared without initial Cabinet approval and after drafting by the Legislative Drafter, be sent by the responsible Minister to the Cabinet with a memorandum explaining the necessity for legislation and showing how the draft meets it. If there is doubt as to whether Cabinet approval is initially required then guidance should be sought from the Secretary to Cabinet.

2.7 Where a proposal to legislate is approved by Cabinet, then Cabinet should, after considering the recommendations reported in the Memorandum, indicate in the conclusions the degree of priority which is to be given to the drafting.

Responsible Officer or Instructor

2.8 Within the responsible department, the Permanent Secretary has the duty to oversee the process from policy development to the preparation of the drafting instructions that will go to the legislative drafter. The Permanent Secretary, or his or her delegate, will be the responsible officer or “instructor” for the purpose of instructing the drafter and thereafter working with the legislative drafter on the drafting of the Bill.

2.9 The approach adopted to move the process forward will depend on the nature of the Bill to be drafted. On a relatively minor or simple piece of legislation the Permanent Secretary may undertake the work or delegate it to an officer within the department. On more complex subjects it may be advantageous to assemble a team comprising the Permanent Secretary or his or her delegate, responsible officers, specialist technical assistants and a legal adviser. Legal guidance on the drafting of a Bill may be obtained from the Attorney General’s office. A properly resourced team is vital to the successful preparation of larger and more complex pieces of legislation.

The need for Consultation

2.10 Consistent with best practice in developing legislation, consultation on proposed legislation must occur with relevant parties within government and, where appropriate, with interested parties outside government. Consultation with the Legislative Drafter should also occur at an early stage to ensure that policy can be reflected in legislation.

2.11 It is the responsibility of the Permanent Secretary for the responsible department to identify other departments which may be affected by the proposals and to seek their input by way of consultation or comment. It will normally be evident which departments should be consulted, however officers should consider carefully the impact of their proposals on other departments. The Permanent Secretary should seek the views of the other main interested departments as early as possible.

2.12 Where the subject matter of the proposed new legislation breaks new ground or represents a major change in policy direction, it is vital for agencies to consult with not only those who have expertise in the subject matter, but also, those who are likely to be affected by the proposals and/or have an interest in the matter.

2.13 It is important to identify at an early stage any major opposition to the proposed legislation and the grounds for it, particularly where it may be likely to undermine the effectiveness of the legislation when passed. Of course it is not a requirement that everyone who is consulted about proposed legislative change will be in agreement with the proposals however, if it is discovered that there is a major issue to be overcome, it would be prudent to identify it at an early stage rather than waste time and resources completing the entire process only to have to abandon it as it nears conclusion.

2.14 It is without doubt that laws are more likely to be enforceable amongst a population that generally supports and feels included in the process. Different groups can bring different perspectives to the analysis of the subject which can be productive in helping to tailor legislation better suited to its eventual purpose.

2.15 It should be remembered that a balance must be struck between an adequate consultation process and adherence to the strict ‘need-to-know’ principle. Careful consideration should be given to which individuals, organisations and groups are to be included in the consultation process so that no-one omitted by oversight and that the amount of consultation is at a level which fits the scale and importance of the legislation being proposed.

2.16 Where is however some legislation where it would be unusual for public consultation. This is likely to occur where the legislation: alters fees or benefits only in accordance with the Budget; is for minor machinery provisions that would not fundamentally alter existing legislative arrangements, and where consultation would give the person or organisation consulted an advantage over others not consulted.

2.17 Where consultation is considered necessary then adequate time and funding must be built into the planning of the legislative process. The appropriate timing of, extent of and need for consultation may vary and are matters for judgement. In some cases it may be desirable for consultation to take place on general principles at the time as the policy issues are being developed; in other cases consultation on the draft legislation may be more appropriate. There may be cases where the urgency attached to the legislation will prevent widespread consultation.

Preparing the Bill

2.18 It is to be remembered that the actual drafting of the Bill (the writing of the particular law or amendment in legal language) is specialised work to be carried out by the Legislative Drafter, who is located within the Office of the Attorney General. A good Bill can only result from clear and precise instructions from the instructing department, followed by detailed collaboration between the instructing department and the Legislative Drafter. The process of producing clear instructions is a task in itself.

2.19 The instructing department must produce a clear and detailed statement of what the Bill is to do in policy terms. The policy statement simply sets out what it is intended that the legislation should achieve and the reasons why it is thought to be necessary to introduce it.

2.20 Drafting instructions are prepared by the instructing department on the basis of the policy instructions and they in turn are used by the Legislative Drafter as the basis for drafting the Bill to be presented to Parliament. The main purpose of drafting instructions is to indicate what is wanted and to tell the Drafter the detailed reasons behind the various proposals.

2.21The basic legal concepts must be identified, particularly with a Bill that is addressing a matter which has not been covered before. The existing state of the law should be set out in outline and mention should be made of relevant cases decided in the courts as well as the statutory provisions.

2.22 The translation of policy into instructions can often highlight points which may not have been considered in detail previously or identify an inconsistency in the policy. The instructions may need to go through several drafts before these points are addressed and they are ready to be sent to the Legislative Drafter. It is essential that adequate time be allowed for this process. Poorly drafted, or inadequately thought-through instructions can cost time and frustration later in the drafting process.

2.23 Clear drafting instructions will also assist in the preparation of an Explanatory Memorandum which is to accompany the Bill to assist Ministers and Members with understanding the provisions and proposed effects of the Bill.

Submitting instructions to the Legislative Drafter

2.24 Where possible all the instructions for a Bill should be sent to the Legislative Drafter at the same time, although it is recognised that this may not always be possible. A copy of the instructions and all of the accompanying documents should be sent to the Legislative Drafter and thereafter all communication should be between the Legislative Drafter and the responsible officer within the instructing department. However, the Legislative Drafter may also wish to meet with other members of the instructing department (for example technical officers) or possibly the Minister during the drafting process if he considers it necessary.

2.25 The Legislative Drafter will send clauses to the responsible officer within the instructing department, who should then circulate them to those concerned, including other departments. It is possible that they may want to request changes to the draft clauses. The process of drafting, consideration and discussion of drafts and re-drafting goes on until the Bill is in a form suitable for introduction into Parliament.

Importance of Clarity

2.26 To reduce the risk of challenge, legislation should be expressed in the clearest possible language. Courts are reluctant to interfere with an action which is clearly in accordance with the express wish of Parliament. Therefore it is very important that legal advisors and legislative drafters are alerted to aspects of policy which are likely to attract opposition, so that the draftsman can focus on the likely areas of technical challenge. It may even be necessary in cases of particular difficulty to take specialist advice from legal experts in the field.

Explanatory Memorandum

2.27 References to an Explanatory Memorandum are found in the Standing Orders of the Parliament, viz. Order 43 (6) states that “An Explanatory Memorandum stating the contents and objects of the Bill in non-technical language shall be attached to the Bill.” The Administrative Procedures document of pre-independence days refers to a statement of ‘Objects and Reasons’ but this term is not found in the Standing Orders and it appears is simply another expression used to describe the purpose of the Explanatory Memorandum. Therefore it should now be noted that the Explanatory Memorandum will, amongst other things, set out what are the objects of the Bill and the reasons for introducing it. In some other jurisdictions the Explanatory Memorandum is referred to as ‘Explanatory Notes’. To avoid confusion by using several different terms for the same thing, it is recommended that officers use the same term as that used in the Standing Orders of the Parliament.

2.28 The Explanatory Memorandum, containing notes explaining the Bill, is prepared by the department in consultation with the Legislative Drafter. That is, the Legislative Drafter will check and approve the Memorandum prior to publication to ensure that it complies with the undernoted requirements.

2.29 The purpose of the Memorandum is to explain, and to help the reader understand, what the Bill does (but not why it does it), how it does it and to provide helpful background. It is also designed to inform Parliament and others of the main impact on public expenditure or public service manpower, on business, charities, the voluntary sector and the environment.

2.30 The Memorandum must be a neutral account of the Bill not an attempt to ‘sell’ or to promote it. It should also not attempt to give the impression that the Bill does more or less than it actually does. This is not just a question of not misleading the reader: the Courts may consult the Explanatory Memorandum when deciding future cases. It must be ready to accompany the Bill when it is first presented to Cabinet for consideration.

2.31There are no fixed rules governing the contents of the body of the Memorandum and exactly what is covered will depend on the Bill. But it should usually contain:

· Summary and background - these should give a reader without legal training and with no great knowledge of matters covered by the Bill sufficient information to grasp what the legislation is about. It should explain briefly what the legislation does and its purpose, including any relevant background and describe in broad terms how the legislation goes about achieving its aims. A useful approach is to describe the present situation and how the Bill would change it.

· Overview of the structure - this should provide a summary of the Bill’s structure, although this may not be necessary for short Bills.

· Territorial extent – this should identify whether the Bill is to apply to the whole of the Solomon Islands or to only part of the country, and if so, to which part.

· Commentary - This section should provide more detailed notes – typically a note on each clause of the Bill. The point is to provide additional information but not to duplicate the legislation or to repeat or paraphrase the words in a clause. It is acceptable to have a single note covering a number of clauses. Some of the things which can be included in the commentary are, for example: factual background; cross references to, and interaction with, other legislation; definitions of technical terms used in the Bill; examples of how the Bill would work in practice; flow charts, diagrams and a glossary of acronyms

· Concluding sections should contain:

· Public sector financial cost – an estimate of the financial consequences of the Bill in terms of total public expenditure. Such costs should normally relate to the full year costs of implementing the new statute;

· Public sector manpower implications – these should forecast any changes in the staffing requirements of Government departments and their agencies which are expected to result from the Bill. This should include forecasts as to requirements during any transitional period.

· Regulatory impact – the Memorandum should contain a summary of the RIA (see below) and a reference to where the full RIA can be found.

· Commencement date – the date that it is intended that the legislation is to come into force should be set out. For example, is it intended that it should come into force on the date of publication in the Gazette or on some later date.

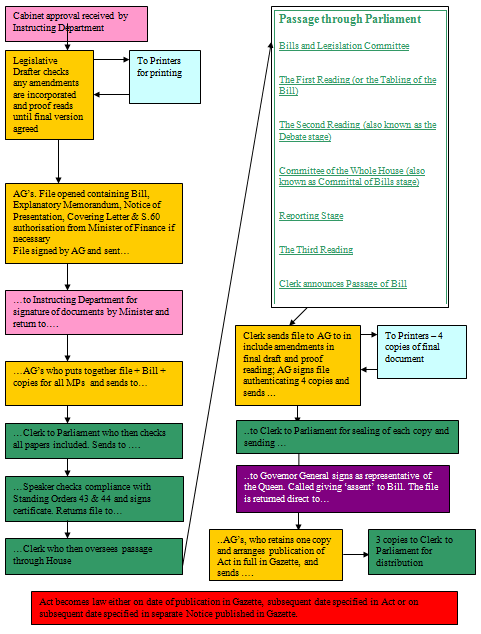

A SUMMARY OF THE LEGISLATION PROCESS PRIOR TO INTRODUCTION OF A BILL IN PARLIAMENT

2.32 Where a Bill amends existing legislation it can be difficult for the reader to work out what the amended legislation will look like and therefore it may be helpful to annex to the Explanatory Memorandum an extract from the existing Act showing how the Bill amends it.

Regulatory Impact Assessment

2.33 A Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) must be produced for any proposal for legislation which has an impact on business, charities and the voluntary sector. An RIA is an analysis of the likely impact of a range of options for implementing policy change. It must set out the risk or problem to be addressed and the options available – including ‘do nothing’ and any regulatory options, such as Codes of Practice or information campaigns. It should also set out the likely costs and benefits of each option. Its aim is to answer the question “Is this the best way of achieving the objective.

2.34 The RIA should be proportional to the likely impact of the proposal. Where the legislation it is likely to affect only a few businesses, or many businesses but to a small degree, then the RIA should be quite short. For more substantial impact, more data and analysis is required. An RIA is developed alongside policy in three stages:

· Initial RIA provides a rough assessment based on what is known. It should include best estimates of the possible risks, benefits and costs.

· Partial RIA contains more detailed policy options and refined estimates of costs and benefits. The partial RIA should be submitted with any proposal needing agreement from Cabinet or other interested Ministers. It must also accompany any formal consultation

· Full or final RIA should reflect the responses from any consultation and include further information and analysis particularly relating to the costs and benefits of the policy proposal, together with clear recommendations. The full RIA should be made available alongside a Bill published in draft for pre-legislative scrutiny, and similarly be made available alongside the Bill when it is introduced in Parliament.

2.35 The RIA shall form part of the Explanatory Memorandum referred to in Order 43 (7) of the Standing Orders to Parliament.

Presentation to Cabinet

2.36 Once the Bill has been drafted, the responsible member of Cabinet shall present it to Cabinet, together with the Explanatory Notes and RIA, under cover of a memorandum commenting on it. If the Cabinet approves the Bill, with or without amendments, it is desirable that in its memorandum a recommendation be made as to which sitting of Parliament the Bill is to be presented.

2.37 As soon as the extract from the Cabinet’s conclusion conveying the approval is available, the Cabinet Office will send out 3 copies of it. One is to be sent to the responsible department; one to the Attorney General, and also one to the Clerk to Parliament by way of notification, so that the Clerk may be kept fully aware of the likely flow of future business. The Attorney General on receipt of his copy of the conclusion from the Cabinet will arrange for the Bill to be printed and a copy sent to the Clerk to Parliament.

Note: the attention of readers is also drawn here to The Standing Orders of the National Parliament of Solomon Islands, Part L – Procedure on Bills. The Standing Orders may be found in Volume 1 of the Laws of Solomon Islands (the Green Books) immediately after the Constitution, at page 115.

3.1 When the Cabinet approval and the Bill are received from the instructing department by the Office of the Attorney General, the Legal Draftsperson checks the Bill to ensure that any amendments required by the Cabinet are incorporated, and the Bill is proof read.

3.2 The Bill is then sent to the Printers for printing. Where possible, an electronic copy of the Bill should be sent to the Printers as this will greatly save on time spent by the Printer having to retype a hard copy. When printed it is returned to the Office of the Attorney General for proof reading and if necessary sent back to the Printers for correction. This process of to-ing and fro-ing between the Printers and the Attorney General’s continues until the final version is agreed to by the Attorney General’s office.

3.3 On receipt of the final agreed version from the Printers, the Office of the Attorney General will open an ‘Introduction File’ into which a copy of the Bill is inserted and which will, from the date of insertion, map each stage of the progress of the Bill until it is passed by Parliament. Also inserted in the file with the Bill are:

(i) the Explanatory Memorandum

(ii) notice of Presentation as required by Order 44 of the Standing Orders of the National Parliament.

(iii) covering letter from the Minister to the Clerk to Parliament

(iv)authorisation from the Minister of Finance under section 60 of the Constitution.

This file is signed by the responsible officer within the Attorney General’s Office to confirm that the relevant papers have been inserted.

3.4 The file is then sent to the Permanent Secretary of the instructing department for the Minister to sign the Explanatory Memorandum, the Notice of Presentation and the covering letter to the Clerk. In cases of urgency this practice may be varied and the file taken direct to the Minister for signing of the documents, but in such a case the Permanent Secretary must be informed.

3.5 Where the file includes section 60 authorisation as mentioned above, it is put before the Minister of Finance for the signing of that document. Once all the documents have been signed the file containing the Bill and documents is first returned to the Attorney General’s Office and is then sent by that office to the Clerk to the Parliament, together with enough copies of the Bill for each Member of Parliament and the various officers likely to require copies plus a few spares.

3.6 When the file is received at Parliament House, the Clerk to Parliament checks that all the papers are included and passes the complete file to the speaker. It is the responsibility of the Speaker to ensure that it is in order and that it complies with Orders 43 and 44 of the Standing Orders. If it does not comply, then the Speaker signs a certificate to that effect and this is placed in the file and the file is returned to the Clerk who takes responsibility for it.

SUMMARY FROM APPROVAL OF THE BILL BY CABINET UNTIL IT HAS BEEN PASSED BY PARLIAMENT

Procedure through the House

3.7 The Bill may first be placed before a Bills and Legislation Committee (otherwise known as the Bills Committee) whose responsibility it is to report on it to Parliament (see Orders 50, 55 and 71 of the Parliamentary Standing Orders). It is desirable that their report be placed before the house at an early stage, if possible before the tabling of the Bill, and certainly before the second reading. This is because the purpose of the report is to help Members in their deliberations during the Second Reading (see below).

3.8 It is a convention that the Bills Committee is usually made up of a Chairman and between three to five Members. The Attorney General, the legislative drafter and the relevant officers from the instructing Department may be called before the Committee to answer questions on the Bill, depending on the complexity of the issues involved. The Committee Secretariat support is provided by the National Parliament Office (see Standing Order 6 (7)).

3.9 Officials and Members should be aware of the existence and operation of Parliamentary Select Committees and how these may impact on the passage of Bills. A detailed explanation may be found in the Parliamentary Handbook and Parliamentary Standing Orders. The passage of the Bill through the Parliament follows certain set stages. These are: The First Reading, The Second Reading and The Third Reading.

3.10. The First Reading. This is also sometimes referred to as the ‘Tabling of the Bill’ and the expression comes from the action of the Bill literally being laid on the table. This is the first time that the Bill is presented to Parliament and is a formal stage when, by way of announcement, the short title of the Bill is read out by the Clerk to Parliament. [Order 47(3)]. The announcement is a hangover from the days in history when there were no printing presses available to print and publish copies of the Bill for distribution to members as notification of business. Indeed in the days before printing was widely available the whole Bill would be read out to the assembled Members to inform them as to what it contained – hence the expression ‘The First Reading’. The terminology used is common to Westminster based legislatures. There is no debate on the Bill during the First Reading. After the formal first reading the Speaker announces that the Bill is set down for its Second Reading.

3.11 The Second Reading. This stage is when the Minister (or if a private member’s Bill, the Member) responsible sets out the principles of the Bill introducing it in the form of a motion as follows: ‘Mr. Speaker Sir, I beg to move that the X Bill be now read a Second time. After moving the motion he continues with his prepared speech on the purpose of the Bill. When the Minister has finished, he will normally end by saying, ‘Mr. Speaker, with these, I beg to move”. The Speaker then says, “It has been moved by the Hon. Minister of YYY that the X Bill be now read a second time. The motion upon this Bill is now open for debate.”

3.12 The Members will then debate until all those who want to, have spoken. The Minister will then make final remarks. If, during the course of debate, members raised questions or concerns, the Minister is expected to answer the questions in these final remarks. At the end of his comments he will say, “…and Mr. Speaker Sir, I beg to move”. The Speaker then says, “I will now put the question: the Question is that The X Bill be now read a second time. Those in favour, please say ‘aye’, and those against say ‘no’”. As soon as the Speaker has collected the voices of the Ayes and the Noes, the question being then fully put no other Member may speak on it. (Standing Order 41)

3.13 If the answer is adjudged to be ‘Yes’ the Speaker will say “The Ayes have it. The X Bill is now committed to the committee of the Whole House.” If according to the Speaker’s judgement as to collection of voices that the Noes have it, and if no Member challenges his statement, he shall declare the question to have been decided. He will say, “That is the end of the Bill. We shall not go any further on it.” (See Standing Order 48 (7))

3.14 Committee of the Whole House, also known as Committal of Bills stage (Order 49 Parliamentary Standing Orders) occurs when the question is put the ‘Ayes’ have it, the House will go into the Committee of the Whole House. At this stage the Clerk will say “Bills – Committee Stage. The X Bill.”, and the Speaker will then say, “We shall now move into the Committee of the Whole House”. The Speaker will then move down from his or her chair to sit with the Clerk at the Clerk’s table. When the Speaker moves down to the Clerk’s table the Serjeant-at-Arms will remove the Mace from the table place it under the table. The Mace will remain in this position during the whole committee stage.

3.15 The Speaker, who is now sitting at the Clerk’s table, becomes the Chairman and he will say “We are now in the Committee of the Whole House to consider The X Bill.” The Bill is then considered clause by clause, (Standing Order 52), with Members making specific comments relating to each clause as debate proceeds.[2] Amendments can be suggested and requested at this stage, but any proposed amendments must be agreed to by the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Under the provisions of Order 51, 24 hours notice must be given of amendments otherwise they may not be moved. In addition if a proposed amendment does not satisfy the requirements of Order 51, the Speaker may order its withdrawal from consideration.

3.16 Again during this stage Members may want to ask questions about the Bill and Ministers (or where relevant the Attorney General) must be in a position to provide answers. It is therefore imperative that the Ministers themselves are provided with the correct information in anticipation of questions in advance. In addition, during this stage, Permanent Secretaries, and such other technical officers as have specialist knowledge relating to the Bill, should be present to supply supplementary information to the Minister if required.

3.17 The preamble to the Bill is the final part of the Bill to be considered and at the conclusion of this discussion the Chairman resumes his position in the Speaker’s Chair and resumes Parliament. The Mace is returned to its original position.

3.18 The Report Stage: After the announcement that Parliament is resumed, the Minister will stand and say “Mr. Speaker Sir, I beg to report that The X Bill has passed through its committee stage without amendments (or with amendments, if amendments have been made and accepted at committee stage).

3.19 The House reconsiders it, and may debate any amendments that have been made, or new clauses that have been inserted in committee. However, no new amendments can be moved. If additional amendments are sought, they must be given to the Clerk who will circulate it or them in a Notice Paper. After the Minister has finished reporting, the Speaker will say, “The X Bill is now deemed to be set down for the Third Reading”.

3.20 The Clerk will then say, “Bills – Third Reading. The X Bill. ”After the Clerk has announced the Third Reading of the X Bill, the Minister will say, “Mr. Speaker. Sir, I beg to move that the X Bill without amendments (or with amendments) be now read a third time and do pass.” The Speaker then says, “The question now is that The X Bill without (or with) amendments be now read a third time and do pass. Will those in favour” etc., etc. as above. The Clerk will then declare the passage of the Bill by announcing the title of the Bill.

3.21 For appropriation Bills, the procedure in committee is the same as that described above except that the Committee of the Whole House is termed ‘Committee of Supply’. For financial procedures relating to presentation and second reading of appropriation Bills and supplementary appropriation Bills, see Standing Orders 61-67.

3.22 The Third Reading. At this stage the Minister responsible stands and formally asks for the Bill to be considered a third time – “Mr Speaker I beg to move that X Bill be now read a third time and do pass.” The Speaker will announce, “It has been moved by the Minister that the Bill be read for a third time and do pass. All those in favour say “Aye” and those against say “No”. The “Ayes” and “Noes” are then ‘counted’ by collection of voice, that is, the Speaker according to his own judgement states whether he thinks there are more “Ayes” than “Noes’ or vice versa. If a Member thinks that the Speaker has got it wrong then he may ask for (claim) a division. If a division is claimed then each Member is called in turn by name and asked to give his vote by stating “Aye” or “No” and the Clerk shall record the number of votes and the number of abstentions and declare the result of the division. [Orders 41 and 42]

3.23 Then the Clerk announces the passage of the Bill by reading its short title and that it has been passed by Parliament, and writes at the end of the Bill the words: ‘Passed by the National Parliament of Solomon Islands this day” giving the date. [Order 58(3)] The Clerk then signs the folder and delivers it to the Attorney General.

3.24 It is responsibility of the Attorney General to examine the file to find out if any amendments have been agreed to and to arrange for their inclusion in the final draft. Once this process is complete, the Bill is sent to the printer. Four copies only of the Bill are printed at this stage for the Governor General to sign and they too are inserted into the file. The file is signed by the Attorney General and the Legislative Drafter as evidence of compliance with procedures. The four copies are then sent to the Clerk to Parliament to be sealed and are then forwarded to Government House for assent by the Governor General. Assent might be defined as ‘official consent’ and it is demonstrated by signing of the sealed copies of the Bill.

3.25 By virtue of section 27 of the Constitution, the Governor General is the representative of the Head of State in the Solomon Islands. The Head of State is her Majesty The Queen and therefore the Governor General assents to Bills on her behalf. This is provided for in section 59 (2) of the Constitution: “when a Bill has been passed by Parliament it shall be presented to the Governor-General who shall assent to it forthwith on behalf of the Head of State, and when such assent is given the Bill shall become law”, although section 59 (3) provides that it does not come into operation until it is published in the Gazette.

3.26 After assent and the file being returned to the Office of the Attorney General, the Attorney General retains one copy and the file is then sent to the Clerk to Parliament to distribute the three remaining copies. Finally, the Attorney General either verbally or by note requests the Printer to publish the Act in the next publication of the Solomon Island Gazette.

3.27 Once the Bill has been passed by Parliament it is known as an Act, but it does not become law until it is assented to by the Governor General and it does not come into operation until it is published in full in the Gazette or at a later date appointed by notice (known as a ‘Notice of Commencement’) which also must be published in the Gazette. It should also be noted that parts of an Act may be brought into force at different times. If parts of an Act are to be brought into force at a later time then a notice must be published in the Gazette appointing the time(s) when each additional part is to come into force. Guidance as to the necessity for and in the preparation of Notices of Commencement may be obtained from the office of the Attorney General.

4.1 Subsidiary legislation is law made under powers contained in Primary Legislation. The term is defined in the Interpretation and General Provisions Act of 1978 (Cap.85), section 61(1) as:

“any legislative provision (including a delegation of powers or duties) made in exercise of any power in that behalf conferred by any Act, by way of by-law, notice, order, proclamation, regulation, rule, rule of court or other instrument”.

To put it another way, the power to makes rules, regulations, by-laws must be set out in an Act of Parliament. It is the Constitution which gives the power to the National Legislature (the National Parliament) to make laws which apply to the whole country and in turn the National Legislature can delegate power to make certain rules, regulations, orders etc to certain office holders such as Ministers. A common example is the power often given in an Act to a Minister to make regulations in respect of certain matters which are listed in the Act. This power is a delegated power and it only operates in respect of those matters listed in the Act.

4.2 Like Primary Legislation, Subsidiary legislation is also required to be published in the Gazette and shall only come into operation on the date of such publication or on such other date as may be provided therein.

4.3 The Chief Justice in the case of Quan –v- Minister of Finance & Treasury, HC-CC 151 of 2005, has given detailed consideration to what constitutes subsidiary legislation within the meaning of the above quoted section 61(1) of the Interpretation and General Provisions Act. His Lordship stated:

“Subsidiary legislation is more commonly referred to as ‘Delegated legislation’. The underlying concept behind the use of such types of legislation is that the legislature delegates because it cannot directly exert its will in every detail. All it can do in practice is to lay down the outline.”

4.4 Whilst by-laws or regulations might quite obviously be subsidiary legislation it is notable that orders or notices can be either ‘legislative’ or ‘administrative’ in character and it can be quite difficult to assess into which category a particular order or notice falls. It is confusing enough to have given rise to many court cases in several jurisdictions. In the case of Commonwealth v Grunseit (1943) 67 CLR 58, an Australian case quoted by CJ Palmer in the Quan case, Latham CJ observed:

“the general distinction between legislation and the execution of legislation is that legislation determines the content of a law as a rule of conduct or a declaration as to a power, right or duty, whereas executive authority applies the law in particular cases.”

Therefore, in the case of Quan, it was decided that a Notice naming persons appointed to a Board was of an executive rather than a legislative character and as such did not require publication in the SI Gazette for the appointment to become lawful. The legislative action had already been taken when Parliament put the power to appoint into the hands of the Minister to exercise in his sole discretion, and therefore his exercise of that power was an executive action.

4.5 As a matter of good practice and public information it may still be necessary to publish the Notice as a Gazette Notice as opposed to a Legal Notice in the Solomon Islands Gazette.

4.6 Some examples of delegated powers to make subsidiary legislation are:

![]() Section 4 of the Public Service Act of 1988 (Cap.92) gives powers to the

Minister to make rules for a variety of matters including “for the

allocation to or use, care and custody of Government property by public

officers and employees of the Government;”, and it would be under this

power that ‘The Public Service (Government Properties) (Vehicles and

Plants) Rules’ of 1992 were made. It is interesting to note that section

4 also provides that under this Act the delegated power must be

exercised in consultation with the Public Service Commission. Therefore

the PSC must be involved in deciding what goes into the subsidiary

legislation under the Public Service Act.

Section 4 of the Public Service Act of 1988 (Cap.92) gives powers to the

Minister to make rules for a variety of matters including “for the

allocation to or use, care and custody of Government property by public

officers and employees of the Government;”, and it would be under this

power that ‘The Public Service (Government Properties) (Vehicles and

Plants) Rules’ of 1992 were made. It is interesting to note that section

4 also provides that under this Act the delegated power must be

exercised in consultation with the Public Service Commission. Therefore

the PSC must be involved in deciding what goes into the subsidiary

legislation under the Public Service Act.

![]() More than one type of power can be contained within the same Act – thus

in the Delimitation of Marine Waters Act, at section 2 the Minister is

given the power to declare by Order certain groups of

islands as an archipelago. This was done in 1979 by the ‘Declaration of

Archipelagos of Solomon Islands’. Section 11 of the same Act also gives

power to the Minister to make regulations, in accordance with

international law, for, amongst other things, “regulating the conduct of

scientific research with the exclusive economic zone”. Regulations were

made under this power in 1994 called The Delimitation of Marine Waters

(Marine Scientific Research) Regulations.

More than one type of power can be contained within the same Act – thus

in the Delimitation of Marine Waters Act, at section 2 the Minister is

given the power to declare by Order certain groups of

islands as an archipelago. This was done in 1979 by the ‘Declaration of

Archipelagos of Solomon Islands’. Section 11 of the same Act also gives

power to the Minister to make regulations, in accordance with

international law, for, amongst other things, “regulating the conduct of

scientific research with the exclusive economic zone”. Regulations were

made under this power in 1994 called The Delimitation of Marine Waters

(Marine Scientific Research) Regulations.

![]() In the Land and Titles Act, there are a range of delegated powers to

make subsidiary legislation. In section 242 power is given to the

Commissioner of Lands, subject to certain conditions, to declare

that land held in his name is customary land. This section is often used

to return land from ‘alienated’ to ‘customary’ status. Section 250 gives

power to the Minister to make a preservation order over

land considered to be of historic, architectural, traditional, artistic,

archaeological, botanical or religious interest, and placing the land

under his protection. Section 255 gives power to the Chief Justice

to establish Customary Land Appeal Courts by warrant. Section 260

gives power to the Minister to make regulations, and

various regulations have been made by Ministers under this power.

In the Land and Titles Act, there are a range of delegated powers to

make subsidiary legislation. In section 242 power is given to the

Commissioner of Lands, subject to certain conditions, to declare

that land held in his name is customary land. This section is often used

to return land from ‘alienated’ to ‘customary’ status. Section 250 gives

power to the Minister to make a preservation order over

land considered to be of historic, architectural, traditional, artistic,

archaeological, botanical or religious interest, and placing the land

under his protection. Section 255 gives power to the Chief Justice

to establish Customary Land Appeal Courts by warrant. Section 260

gives power to the Minister to make regulations, and

various regulations have been made by Ministers under this power.

How Subsidiary Legislation is made

4.7 The method to be adopted for the making of subsidiary legislation will largely depend on the nature and complexity of the legislation. When a Ministry requires subsidiary legislation the Permanent Secretary of the relevant department shall send a request to the Office of the Attorney General setting out the details of what is required and all relevant information to enable the Office of the Attorney General, and if necessary the Legislative Drafter, to prepare the Instrument.

4.8 If the subsidiary legislation required constitutes a change in policy, Cabinet approval should first be obtained and then submitted with the request. If the subsidiary legislation consists of complex and/or lengthy regulations then detailed drafting instructions will need to be prepared and submitted with the request.

4.9 Many pieces of subsidiary legislation are fairly routine and are contained in short instruments, such as for example Notices of Commencement; Appointments of Commissioners under the Oaths Act or nomination of a date for an election. These follow a set form of words and are quickly and easily prepared by the office of the Attorney General on receipt of the necessary request and information from the instructing Ministry.

4.10 Given the difficulty in distinguishing between legislative and executive acts all Notices and Orders etc should be sent for preparation or for checking to the Attorney General’s Office for determination as to whether publication is required as a Legal Notice in the Gazette.

4.11 It is important to note that all instruments of appointment and / or revocation and so forth are also drafted by the Office of the Attorney General at the request of the responsible Ministry. The supporting rationale for this procedure is that it allows for the oversight of the process by the Attorney General and helps to ensure that such notices as are prepared are consistent with previously Gazetted Notices.

4.12 Once the relevant Instrument has been drafted by the Office of the Attorney General, (or by the Legislative Drafter if it is a more complex set of regulations for example) it is returned to the department for approval. Again, for more complex rules the Instrument may travel between the instructing Department and the Office of the Attorney General and / or Legislative Drafter several times until it is finally agreed.

4.13 When agreed final copies are prepared by the Office of the Attorney General and three are sent to the instructing department for signing by the Minister who is imbued with the legislation making power by the governing Act. By virtue of the provisions of section 35 of the Interpretation and General Provisions Act, this power to make subsidiary legislation cannot be delegated.

4.14 It is only the appointed Minister and not a supervising Minister who may sign the instrument. If the Minister is away or unable to sign for any reason and a supervising Minister is overseeing the affairs of the Ministry, then the instrument shall have to wait for the return of the Minister so that it can be signed.

4.15 After signing, the Ministry keeps one signed copy of the instrument and sends two copies to the Cabinet office. When it receives the two copies the Cabinet office sends one back to the office of the Attorney General for a final vetting as to accuracy and for designation as to whether the instrument is to be gazetted as a Legal or ordinary Gazette notice. When this is returned by the Attorney General’s office, one copy is kept in the Cabinet office and the other is then sent to the Government Printer for printing.

4.16 Under the Constitution, the Governor General also has powers to make subsidiary legislation, in certain specified circumstances, on the advice of the Prime Minister. For example, it is the Governor General acting on the advice of the Prime Minister who assigns responsibilities to Ministers, and also he has the power under the Constitution to declare a Public State of Emergency, and under the Emergency Powers Act to make regulations for dealing with such a situation as exists while the Public State of Emergency is in place. For Instruments emanating from the Office of the Governor General therefore, Government House sends the request for drafting to the Office of the Attorney General. When drafted, the Attorney General’s Office sends it to the Secretary of the Prime Minister who in turn sends it direct to Government House for signing by the Governor General. If it is an urgent matter the Attorney General’s office will send straight to Government House for signing.

4.17 By virtue of section 28 of the Constitution, if the Governor General is absent from Solomon Islands or unable to perform the functions of the office for any reason, then those functions may be performed by the Speaker or if s/he is not available, then by the Chief Justice. However, again by virtue of the Interpretation and General Provisions Act the power to make subsidiary legislation cannot be delegated and therefore it is only the Governor General himself who may sign the instrument of subsidiary legislation.

4.18 All subsidiary legislation, as for primary legislation, must also be Gazetted. Also, as for primary legislation, a copy of the Gazette containing the instrument is evidence of the making of the subsidiary legislation.

Laying before Parliament

4.19 Once an instrument has been Gazetted, unless it has been previously approved by resolution of Parliament, it must then be laid before Parliament for a period of 3 months. This is to allow time to Parliament to pass a resolution to annul the subsidiary legislation should it see fit to do so. The validity of anything previously done under the legislation during the intervening period between Gazettal and annulment by Parliament will not be affected.

4.20 This process is a statutory requirement under the Interpretation and General Provisions Act. If this is not observed then it is possible that the subsidiary legislation may be successfully challenged in a court of law as being void and of no effect. It is the responsibility of the Secretary to Cabinet to ensure that subsidiary legislation that is made is sent to the Clerk to Parliament in order that this section may be complied with.

PacLII:

Copyright Policy

| Disclaimers

| Privacy Policy

| Feedback|

Report an error

URL: http://www.paclii.org/sb/legislation-handbook-2005/main.html